Artist Katie Caron created artwork while recovering from a horrific accident. Courtesy of Katie Caron’s website

By Eliza Marie Somers

Finding a creative outlet while recovering from a traumatic brain injury might just be the therapy you are missing. After suffering a horrific accident when a wall fell on her, artist Katie Caron relied on her creativity to help her through a long and painful recovery.

“I was on a lot of pain medication that didn’t allow me to read, but I could be creative, and it really opened up a side of myself that I hadn’t really experienced before,” Caron said during the Sept. 12, 2025, Brain Injury Hope Foundation’s Survivor Series: The Art of Neuro-Anatomy: The Marriage of Art, Science and the Brain.

“This was a very therapeutic process for me, but I didn’t know it at the time,” Caron revealed.

While recovering in a nursing home, Caron, who had just received her master’s degree in fine arts, began taking out her frustrations in her art.

“I couldn't move. I couldn't be free. And so, I kind of took the anger out on the paper. I squeezed the paper, and I opened it up again and saw all the kind of wrinkles that it made. And the wrinkles looked and felt sort of like that injury like that point of contact, that point where the wall broke me. … I ended up probably doing maybe 40 drawings while I was in there.”

Caron moved back to Colorado to be with family while continuing her therapy. She also started teaching at the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design. While rehabbing and teaching she exhibited her drawings called “Mending” at the college.

“I was using art to mend myself, my brain and my body,” she said.

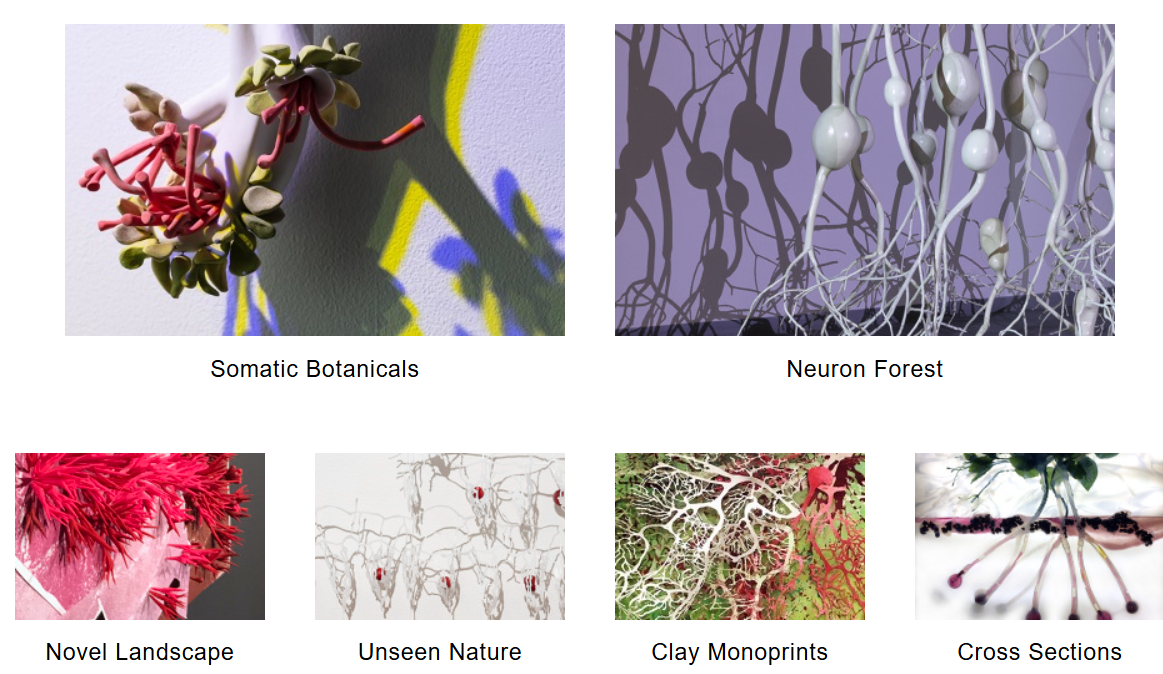

Her experience with a traumatic brain injury also created a desire to understand the brain and resulted in her creating the “Neuron Forest” sculpture. Along with the large project, Caron teamed up with neuroscientist Dr. Maureen Stabio, an associate professor in the Department of Cell and Developmental Biology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Dr. Stabio directs the Modern Human Anatomy Program , a master’s degree program that blends anatomy with 3D visualization and medicine.

For more on the Neuron Forest and the process of making the artwork

https://www.thirdduneproductions.com/cu-anschutz-katie-caron

“When I met Katie, I was so excited because she said, ‘Hey, I want to get people excited about the wonder and beauty of science and nature. Do you want to be a part of this?’ And I'm like, ‘Yes. This is what I try to do in the classroom,’” Stabio said in a video presentation about the Neuron Forest. “The partnership between an artist and a scientist is a win-win, and, in fact, some of the earliest neuroscientists were passionate artists. An example is Santiago Ramon y Cajal, who's considered the father of neuroscience.”

Santiago Ramon y Cajal received the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1906. His drawings of brain cells and neurons are still in use today.

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1906/cajal/article/

- https://www.themarginalian.org/2017/02/23/beautiful-brain-santiago-ramon-y-cajal/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11707675/

“We both want to understand how the world works,” Caron said. “I feel like the artist is investigating it through maybe more of an intuitive and a psychological point of view, and the scientist is investigating it through an analytical mathematical point of view. But I think we're both trying to find the same answers.”

With the Neuron Forest, artist Caron said, “I finally made that thing that caused me that sense of wonder.”

Katie Caron said creating art helped her understand her internal body structure.

Creating the sculpture enabled Caron to “have a visual experience. I feel like my understanding of why my internal body structure looks just like a tree, or looks just like electricity that connects me to the universe … These branching structures are what sort of unites everything. It's almost like an existential religion.”

Stabio explained her passion for neurons and why she has been interested in the brain cells.

“One of the reasons I love neurons so much and why they are so fascinating to me compared with all other cells of the body is that they are electrical,” Stabio explained. “So, your computer is working right now because of the electrons that are running through the wire from your wall to the computer. Neurons are also electrical, and they conduct electricity in a similar way. Instead of carrying electrons, they're carrying ions, essentially sodium, potassium and chloride.

“So, neurons use that electricity to connect and to speak to one another, and to send messages. Your car battery is 12 volts. Your electrical outlet in your wall is 120 volts. In the nervous system, it's a hundred millivolt (a millivolt is 1/1,000 of a volt).

“And in your brain, you have 86 billion neurons, which is I think mind boggling,” Stabio continued. “Each neuron can make thousands of connections to other neurons. They're very chatty. They're very social, and they like to be connected. So, they form networks like Katie showed in her art.”

Interpreting those signals and understanding their code is the “basis of technologies that are healing people today. Like deep brain stimulations, vagal nerve stimulation … Like Elon Musk putting electrodes in the brain.”

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/vagus-nerve-stimulation/about/pac-20384565

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/neuralinks-first-user-describes-life-with-elon-musks-brain-chip/

Because the brain likes to make electrical connections it is possible to rewire the brain after a traumatic brain injury, aka neuroplasticity.

“The brain is one of the most fragile organs of the body, and it is one of the most resilient because it can change, it can learn, and it can adapt. The people who have come through brain injury are testament to that,” Stabio said.

Dr. Maureen Stabio says, the brain is one of the most fragile organs of the body, and it is one of the most resilient because it can change, it can learn, and it can adapt

“The saying that you can't teach an old dog new tricks is wrong because neuroscience has shown the brain continues to be adaptable throughout life. … The pediatric brain is incredibly resilient, and it can rewire to the other side of the brain when there's damage on one side. This is harder to do in an adult. It can still be done, but it's harder, it takes longer, and sometimes we need some support.”

Some of the “support” Stabio alluded to includes research by her colleague Dr. Cristin Welle, professor and vice chair of research for the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, whose lab is exploring the frontiers of neurotechnology, including vagus nerve stimulation.

Welle and her colleagues discovered a direct link between vagus nerve stimulation and its connection to the learning centers of the brain.

- https://news.cuanschutz.edu/news-stories/study-provides-better-insight-into-the-vagus-nerves-link-to-the-brain

- https://medschool.cuanschutz.edu/physiology/faculty/regular-faculty/cristin-welle-phd

“The idea of being able to move the brain into a state where it’s able to learn new things is important for any disorders that have motor or cognitive impairments,” Welle said in a report on the CU Anschutz website. “Our hope is that vagus nerve stimulation can be paired with ongoing rehabilitation in disorders for patients who are recovering from a stroke, traumatic brain injury, PTSD or a number of other conditions.”

So how can a TBI survivor create those new connections and rewire their brain?

“Practice and learning,” Stabio said. “The more you practice something the stronger the connection gets. Neurons that fire together, wire together. So, doing new things and learning new things.”

Along with learning and practicing new things, exercise is also crucial to the brain.

“Research shows the best thing you can do for the aging brain is cardiovascular exercise,” Stabio cited a recent study that linked reduced risk of dementia with step count. “They say, 4,000 steps a day can reduce your risk of dementia by 25 percent; 10,000 steps a day reduces your risk by 50 percent. Cardiovascular exercise, learning new things, engaging in conversation with people, keeping off the endless scrolling on the cellphone (just like we tell our teenagers), going out to dinner with friends, having conversations and being together in human interaction” all help the brain heal and create new connections.

When asked about the marriage of art, science and the brain, Stabio elaborated: “I have a soft spot for the arts, and I felt like something came alive in me when I got to work with Katie.”

“I see the divine in the human body because of its intrinsic beauty. The awe-inspiring complexity; the hidden patterns; the logic that's behind the order. For example, the fractal patterns in neurons are optimized to maximize the connectivity and minimize the energy requirement on them. We've studied their fractal geometry in the neuroscience field. And so, I have a very strong faith, and when I became a scientist, my faith grew even more because I saw this incredible wonder. … When I look in the microscope, I see the hands of a Creator. How that creative process happened and how long it took is another question for other scientists. I think everybody has their own experience with art and science, and that's been what mine is.”

Caron said: “I'm a naturalist. … And for me, it's really about the abstraction of it, and not the literal nature of it. So, I'm trying to create an abstraction and a metaphor, and an emotion in response to the body, and the nature and the connection between the two. I see myself as an abstract artist. So, for me, it's grounded in science, but also in abstraction.”

Caron finished by encouraging other TBI survivors to explore their creativity while also staying focused on what’s important in life.

“I don't want anyone to ever experience the trauma that I experience, but things happen in life, and you don't know when it's going to happen … Try staying true to yourself -- the things that you care about and not compromising that.

“Sometimes we get caught up in money and class and status. … Don't get distracted by things that aren't really meaningful to you. Like, as Maureen said, we all get very distracted with our phones, and we get distracted with what other people are doing … Follow what interests you and the things that you care about.”

Valuable Medical Research Through Plastination Specimens

Out of respect to brain donors and their families a portion of the September 2025 Survivor Series was not recorded when neuroscientist Dr. Maureen Stabio exhibited brain specimens.

Stabio, who was in the CU Plastination Organ Library lab, first displayed a dissection and plastination of the whole nervous system.

“You can see the brain at the top that sends the messages down the spinal cord. And then these are all of the peripheral nerves exiting the body. So that was a healthy nervous system that we created to teach students about the system as a whole, and how it's connected,” Stabio explained.

- The plastination process replaces water and fat in biological tissues with polymers, creating dry, durable and odorless specimens for anatomical study and display.

The associate professor in the Department of Cell and Developmental Biology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine then displayed several brains, including a donor who had Parkinson’s disease, a brain from a multiple sclerosis patient, a brain from a donor who had a benign brain tumor called a meningioma, and a brain from a stroke patient. Interesting enough Stabio did not have a specimen of an Alzheimer’s patient’s brain as it was lent out to students to study the disease.

However, Stabio showed a 3D brain model from Phineas Gage, the “father of brain injury.”

Gage, a foreman on a railroad construction crew, suffered a severe brain injury in September 1848 when an accidental explosion of a charge he set blew his tamping iron through his head. The tamping iron, which was 3-feet, 7-inches and weighed almost 14 pounds, went through his left cheek and through the top of his head, landing 25-30 yards behind him.

Gage lived until May 1860; however, he was not the same person after the injury. The friendly and likeable Gage became fitful, irreverent, and grossly profane, showing little deference for others, said Dr. John Martyn Harlow, who initially treated Gage.

Gage’s injury and his personality about-face resulted in some of the first medical knowledge gained on the relationship between personality and the brain's frontal lobe. Gage’s brain was eventually donated to Harvard University.

“The Harvard Museum of Anatomy has the CT scan of his skull,” Stabio said. “We downloaded the CT scan and 3D printed it. So, this is an exact 3D printed replica of Phineas Gage’s skull.

“And what we did was make a replica for teaching. So, he survived without all of this brain area, but they said that he was no longer Gage. Again, he had changed. And that's because the personality and decision making, and your inhibition holding you back from saying something you shouldn't say is in the frontal lobe. And that was the area that was damaged.”

- For more on the CU Plastination Library visit https://www.anatomylibrary.org/

Dr. Maureen Stabio started the CU Plastination Library in 2016 as a collection of brains for Brain Awareness Week. It has expanded to and it has expanded to include organs of all systems - healthy, diseased, and anomalous cases. Specimens are shared through a lending library system that has served over 9,000 students.