Deb Finegold uses the Energy Reserve pie chart or the “spoon theory” to explain the fatigue she experiences after a TBI.

By Eliza Marie Somers

Honest communication is a major component to a successful relationship. It is even more important if someone in your sphere has suffered a traumatic brain injury, because a TBI can create changes in the way a survivor talks, thinks and behaves.

“Communication is huge,” said counselor Rita Coalson during the April 11, 2025, Brain Injury Hope Foundation’s Survivor Series: Family Dynamic & Your Brain Injury. “Communication has to slow down. It has to change. We have to use simple language a little bit more.”

Joining Coalson on the panel were Dr. Jose Reyes and Iris Reyes; Len and Deb Finegold, Olivia Kunevicius and Carly Rossi.

Deb Finegold described how difficult it was to communicate after she suffered a TBI.

“In the beginning, it’s hard to communicate because you don’t say the things you mean to be saying, and you’ll say weird stuff,” she explained. “You forget things, and you repeat the same thing over and over and over again. But you don’t realize you’ve told the person that already seven times.”

Olivia Kunevicius became one of several caregivers to her sister, Jessica, after she suffered a heart attack that led to an anoxic brain injury – when the brain is deprived of oxygen.

Olivia Kunevicius said when there are several care partners strive for harmony and have honest conversations to avoid conflict.

“When she woke up (from a two-week coma), she couldn’t speak … And so that’s where we started this brain injury rehab journey,” Kunevicius said.” We went through a whole inpatient journey at Craig Hospital relearning everything almost as if like a rebirth, because it felt like she literally had to relearn every single thing again.”

Kunevicius said she had to guess what her sister was thinking and, in the process, gained more patience as a caregiver or care partner.

“I would be the person to explain to all of our friends to give her a little bit more time to answer a question. You know she’s not going respond as quickly as she used to, or let’s take it a little bit slower,” she said. And let’s not hang out in a group of 10 people. Let’s hang out in a group of three people.

“I realized that no one else in our world had any experience with (TBI). So, I was just helping people really understand. And people were really understanding once they knew what her new situation was.”

When there are several care partners friction can rise to the surface. Kunevicius said having a difficult conversation with brother-in-law allowed the family members to work together more effectively for Jessica.

“Be cognizant of your relationships with the other people in your family that are caregivers, because I feel like there needs to be harmony,” she said. “I was working with my brother-in-law, and over time he started to drive me literally insane because I was more of a pusher/doer, and he was, I thought, to be a little bit more enabling.

“And I realized I was stressing Jessica out because she could tell that I had this kind of conflict going with him. So, I made myself have some really difficult heart-to-heart conversations with him, which cleared the air, which helped all of us in general. It was hard to do, because I had never had that situation with him in 20 years of knowing him. Difficult conversations sometimes can be really therapeutic amongst the family members, because when we’re fighting, it’s definitely not helping the person with the injury, because they can tell.”

“Knowing the situation” — as Kunevicius put it– can go a long way in creating a smoother road when it comes to relationships. Many friends and family members don’t realize the impact of a TBI, which can cause strains in close ties.

- Relationships after a TBI

- https://msktc.org/tbi/factsheets/relationships-after-traumatic-brain-injury

One result of a TBI is a fatigue, and this is not your ordinary fatigue that everyone deals with from time to time. TBI fatigue is debilitating causing the survivor to be unable to do daily activities such as laundry or cooking, along with missing family functions and other social events. It’s as if the survivor is living in the slow lane.

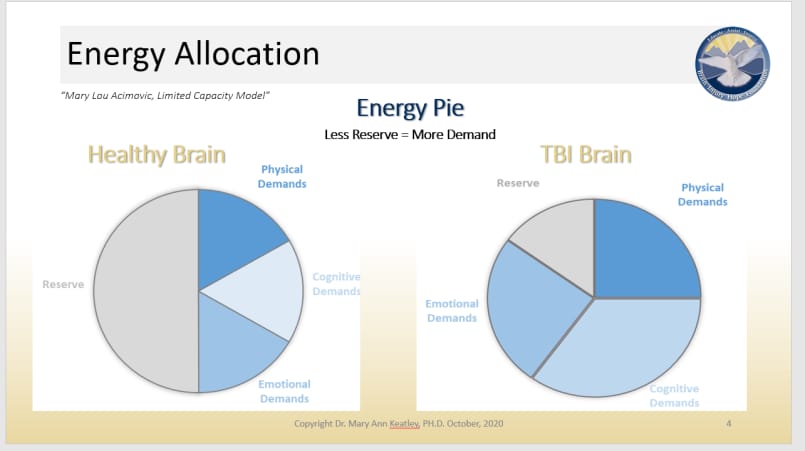

Deb Finegold uses the “spoon theory” or Energy Reserve pie chart to explain the fatigue she experiences with family and friends.

The spoon method equates energy to the number of spoons you have when you wake up, say five spoons. A person with a healthy brain may have three spoons of energy left at the end of the day, whereas a TBI survivor may have one spoon or just a half of a spoon of energy at the end of the day.

“If it’s a bad day, it may take three of those spoons just to get dressed. Another one to eat. So, are you going to be driving that day? Probably not. You might need help with your meals that day,” Deb Finegold said.

It was a concept her daughter and mother learned, which made it easier for them to understand and adapt Deb’s pace.

“Deb was accustomed to doing an unbelievable load on any given day, and then all of a sudden to have it change in a screeching halt to having to be very careful in conserving mental powers,” said her husband, Len Finegold. “Where I was accustomed to doing things at her same pace, to all of a sudden accept: Ah! The pace has changed!

“Everyone’s got the pace. They’re driving down the road to 90 miles an hour, and if you’re in front of them they’re going to honk,” Len explained. “So, in my life I’ve learned Hey, you know what? I don’t have to be in the fast line. I’ll go in lane number 2 or lane number 3. And enjoy life along the way with the people I’m going with. And when things get a little dicey, you know what, that’s just part of life.”

The life changes after a family member sustains a brain injury can cause added stress in an already stressful society. Some of these stressors include multiple doctor appointments, physical difficulties, unforeseen financial problems and relationship changes.

“There’s so many aspects of stress of what one goes through, especially after your loved one goes through traumatic brain injury,” Iris Reyes explained, and it never crossed her mind that she would have to care for her husband, Jose, after he suffered a TBI.

“I had no idea what that world was,” she said. “I had heard of concussions, but I didn’t really know any of the outcomes or the effects of a brain injury. And so, I was definitely immersed into a process that you just learn how to cope with one day at a time, one moment at a time. I was in shock. So, the immediate thing was what are my priorities?

“At that moment my personal self-care was not a priority. You know my priority was to take care of Jose and being his voice. And the decisions were not only his care but also our home life. What did that look like? And how that impacted my own profession, how to continue working because everything came to a halt.”

Jose Reyes said living in the present moment is the biggest lesson he has learned from his brain injury.

It’s been nine years since Jose’s injury and one thing he has learned is that a TBI is not just an injury to the survivor, it is also an injury that affects family and friends.

“I came to the realization of how much this is not an injury for me, but it’s an injury for everybody that cares for you, and loves you,” Jose explained. “I often say that the injury is tough for the person that has it, but I think it’s worse for the person that is a caretaker. Because you’re having to take care of the person and all the other things that are loose. And then on top of that, people will look at you (the caregiver) and say, Well, you got to take care of yourself now.”

Jose and Iris now help mentor other TBI survivors and their families through a peer mentoring program at Craig Hospital.

“That’s been an amazing thing for me to be able to be in a position to be there for other people that have gone through a similar injury,” Jose said. “As Iris said, it’s very true when you see one injury, you see one injury. So, everybody’s different. But the fact that they’ve opened themselves to this work has been really, really healing for me. Plus, it has helped me to meet some wonderful people in the process that are part of my recovery.”

Iris also benefits from the peer mentoring program and the interaction with community.

“It’s helped me tremendously,” Iris said. “A recreational therapist that had been working with Jose really helped us go back into the community. … and we started getting to know and meet other caregivers, other alumni that had gone through similar situations, although different. And we came to bond because of shared experiences. We were able to share resources and have an understanding of what one goes through during this experience that it was so helpful.”

Developing a community and socializing after a TBI might not be priority No. 1, but it’s a critical part of recovery as it boosts mental and physical well-being.

Carly Rossi, LCWS, works with stroke survivors and their families by facilitating community support groups at St. Anthony’s Hospital in Lakewood, Colorado.

Carly Rossi, LCWS, helps stroke survivors return and rebuild community at St. Anthony’s Hospital in Lakewood, Colorado.

Carly Rossi, LCWS, helps stroke survivors return and rebuild community at St. Anthony’s Hospital in Lakewood, Colorado.

“The biggest thing that I find in working with stroke survivors and people with acquired brain injuries and even traumatic brain injury is how to transition back in the community,” Rossi said. “Being a survivor, and what that looks like doesn’t just end with discharge. And so, you’re just kind of left to fend for yourself. This is where I think the community and the connection, and the relationship building is so dire, and so important to be able to find that support.

“The rehab phase offers a lot of hope because it builds more structure. You get some of that structure back in your life with routine, and you still have this care team around you that’s helping you work toward those daily active needs, those basic functions. And you start to make that progress.

“But it also is where grief really starts and fear – What am I going to get back? It’s so much harder than I thought it would be — and I think family starts to harbor a lot of that.

“I have worked in this field for over a decade, but I’m never going to understand the same way that a survivor is going to understand. And so, the peer support work that Jose does, and for care partners doing peer support for each other, it’s so, so important. Part of the work that I do is creating those communities, creating support groups for both caregivers and survivors.

“It’s empowering. And when we think of family dynamics — families post injury, post stroke –this is all about how we’re doing and navigating together.”

Rossi mentioned grief during the rehabilitation process, and it’s important to acknowledge that grief in order to move forward in recovery.

“What I have discovered with grief is that it’s very similar to when you have a brain injury,” Coalson explained. “Because you are grieving who you were; who you’re not. And your family members are all grieving. Your world has changed, and you want it to go back to the way it used to be, and you don’t even know what it’s supposed to be. The other thing is, the unknown is, it brings on a lot of fears.

Counselor Rita Coalson stressed the importance of addressing anger issues after a TBI.

Counselor Rita Coalson stressed the importance of addressing anger issues after a TBI.

“But we don’t necessarily think about having a brain injury with grief. We don’t really acknowledge that. But if we did, it would be amazing if we could do that more often.”

Coalson said it is like disenfranchised grief – grief that doesn’t fit society’s attitude about dealing with loss.

“Disenfranchised grief is when you see somebody with a brain injury they could be fine looking, no one thinks there’s a difference, but inside that person has completely changed and their world has changed as well. So, they can’t really grieve or say much about it because people think they are fine. … So, there’s a lot of anger, lots of anger, due to injustice, and a lot of sadness. … And then the fear kind of sets in. That’s all part of grief, because it’s an unknown. Your world’s no longer safe. You don’t feel protected like you used to. It’s a scary world out there.”

Coalson explained some techniques to help with anger issues, such as yelling into a pillow, hitting a punching bag, or taking a black or red crayon and scribble with it until it’s gone. She also said it’s important to verbalize the anger by stating what you are angry about when doing these exercises.

“What you’re trying to do is just move the emotion because anger is a high emotion,” she said. “We have to kind of move it and get it out of our system because it’s there. Even if you think it’s not there, it is there.”

Tips for relationships

Rita Coalson: Have a backup plan. Learn to set boundaries, to say no, because what you’re trying to do is protect your energy. You’re the one that has less energy. You’re the one that has less motivation. You’re the one that’s dealing with your internal struggle in such a huge, gigantic way, but so are your loved ones.

Jose Reyes: Something that I learned, and this was said to me by someone in the hospital: This is going to help you live in the present. And I looked at this person, I do remember thinking you don’t know what you’re talking about. But that’s been the most amazing lesson from this injury is that I used to live in the future or the past. Now I got to live in the present. And there’s many things that happen in the present that I missed because I was thinking about the future.

Iris Reyes: Self-care is for me the priority as a care partner because if you don’t have much of a reserve yourself it’s hard to extend any grace to your loved one. So, I would say, the first thing is incorporate self-care — daily self-care. It could be just even moments of getting away and breathing, or listening to some music.

Deb Finegold: The start of my actual recovery was when I decided that I wasn’t a victim. I was a person, and I was a survivor. This was the new, me, and it’s just OK. It’s OK, and absolutely, you live in the present.

Len Finegold: You know it’s the same old thing that people have said many times over and over again: Don’t forget to put your oxygen mask on first because if you don’t take care of yourself, you’re not going to be able to take care of anybody.

Carly Rossi: The saying that just keeps coming to my mind is: Growing through what you’re going through.

Olivia Kunevicius: As a family member, I know the only way I got through everything was becoming an expert at compartmentalizing. … Just acknowledging how hard it is and to find that space to process what happened.

One thing everyone agreed upon was laughter can help family dynamics and relationships. Shared humor is powerful and effective in healing disagreements, hurts and resentments by creating positive feelings and emotions. So, go ahead and laugh at your mistakes. Watch a comedy. Laugh or smile at a puppy, kitty or child playing.

Being a TBI survivor is a life-long journey, and with effective communication, laughter and a positive community you can smooth over the potholes and obstacles on the highway of life.